Toku Reo Toku Ohooho - My Language, My Awakening

One of the strands of enquiry I have been pursuing during my time here in Vanuatu is how languages are fostered here, both at home, and within the education system.

It's necessary to provide some background information before we begin to delve into this discussion.

Vanuatu was previously known as the New Hebrides before gaining its independence from the shared English/French administration on 30 July 1980.

Vanuatu, the name, comes from two words put together - 'Vanua' (meaning land, or home - similar to 'whenua' in Maori) and 'tu' (meaning to stand - yet another connection to te reo Maori).

According to Wikipedia Vanuatu has a population of 243,304.

A recent study of the languages of Vanuatu informs us that this island nation's three official languages – Bislama , French and English – were all introduced during European colonisation. Vanuatu is also home to a wealth of vernacular languages which were inherited from pre-colonial times, and are still spoken to this day. Altogether, the country counts 138 distinct vernacular languages.

This makes Vanuatu the country with the highest density of languages per capita in the world.

My mother speaks bislama, and four of the languages from our island Tanna.

Bislama is the major common language spoken by most people in Vanuatu. Whilst there is a small percentage of Ni-Vanuatu who learn to speak Bislama as a first language, mainly in the urban areas, most learn it as a second language.

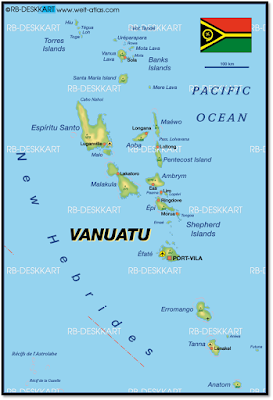

It's a little hard to see, but here's a diagram that gives you an idea of how the languages are spread across the archipelago. You can see that my island of Tanna, which is roughly the size of Lake Taupo, possesses six unique languages alone.

It's necessary to provide some background information before we begin to delve into this discussion.

Vanuatu, the name, comes from two words put together - 'Vanua' (meaning land, or home - similar to 'whenua' in Maori) and 'tu' (meaning to stand - yet another connection to te reo Maori).

According to Wikipedia Vanuatu has a population of 243,304.

A recent study of the languages of Vanuatu informs us that this island nation's three official languages – Bislama , French and English – were all introduced during European colonisation. Vanuatu is also home to a wealth of vernacular languages which were inherited from pre-colonial times, and are still spoken to this day. Altogether, the country counts 138 distinct vernacular languages.

This makes Vanuatu the country with the highest density of languages per capita in the world.

My mother speaks bislama, and four of the languages from our island Tanna.

Bislama is the major common language spoken by most people in Vanuatu. Whilst there is a small percentage of Ni-Vanuatu who learn to speak Bislama as a first language, mainly in the urban areas, most learn it as a second language.

It's a little hard to see, but here's a diagram that gives you an idea of how the languages are spread across the archipelago. You can see that my island of Tanna, which is roughly the size of Lake Taupo, possesses six unique languages alone.

So it's an incredible place to look into language diversity. I have taken part in general conversation with family members here, and at any one time during such discussions there can be up to half a dozen languages being spoken around the conversation circle.

My mind boggles as I ponder the vast depth and range of the benefits of multilingualism, including a superior ability to concentrate, solve problems and focus, better mental flexibility and multitasking skills, and also a preventor of dementia and mental illness.

Furthermore, language being the gateway for culture, multilingualism is therefore a powerful vehicle for ensuring ones connection to culture and sense of identity. It therefore follows that multilingualism grows a resilient soul, and helps to protect against social, mental and physical illness.

"Could it be that the human brain evolved to be multilingual – that those who speak only one language are not exploiting their full potential? And in a world that is losing languages faster than ever – at the current rate of one a fortnight, half our languages will be extinct by the end of the century – what will happen if the current rich diversity of languages disappears and most of us end up speaking only one?" - Gaia Vince

So with the multitude of languages present here, what, then, are the implications for kindergartens and schools, and are their any lessons to be learned from this for education in New Zealand, where we have a growing population of Pasifika communities?

The following is somewhat of a case study to help illustrate how languages are cultivated within the family unit.

Meet my beautiful namesake Numara. Numara is twelve months old now. We share the same custom name from our Great Grandmother.

In her household, her Mum, Dorothy, speaks both her father's language, and her mother's language. Her father Samuel speaks two further languages, his Mother's and his Father's.

Both Dorothy and Samuel also speak Bislama. Bislama is also spoken by Numara's mum and dad, and they also speak English from time to time.

Since Numara's birth, her mum and dad have been teaching her all four (yes four!) of their local languages, as well as Bislama. Throughout Numara's regular care routines, and her wakeful times, she is securely surrounded in the sounds of all five of these languages so she will be well equipped with her home languages by the time she starts Kindy.

It is well recognised here that from birth to three years old children will learn their local, or vernacular languages in the home.

Then, when children start Kindy, Kindy is taught using a mixture of the local language and Bislama. There are implications for families who may have moved away from areas where their languages are spoken to other geographic areas as it means that their child may not have the opportunity to be educated in their family language. If this is the case, then only Bislama will be spoken in the home, which is how language can be lost from generation to generation.

Furthermore, this means that Kindy relies on utilising teachers who are fluent in the local language, in order to maintain the balance between home language and Bislama.

Bislama and local language are then utilised for instruction until Class Three at Primary school where students then begin to learn English and French.

So by the time Numara finishes primary school she will be fluent in all four of her family languages, and in addition to this will be conversant in Bislama, French, and English.

When we transfer this understanding of how language is fostered and maintained in Vanuatu, into the

Aotearoa-New Zealand context, I have great concern for how we can continue to nurture children's home languages in an economic climate that requires parents and whanau to have full time jobs. This concern heightens for me when we know that Pasifika families in particular work long hours, some on minimum wage, in order to provide for their families.

What then becomes of the 'language nest' so to speak that acts as the first and most important language cultivator? How can we offer Pasifika children the opportunity to be educated in their home language (as is their birthright) when we have government policy driven by economic growth at the expense of social and cultural sustainability. Furthermore, how do we nurture these home languages when there is a shortage of teachers with the cultural competencies required?

In Aotearoa-New Zealand we will need a refreshed commitment to nurturing home languages starting in Early childhood and leading all the way to secondary school. We need to seek out and develop working partnerships with Pasifika community leaders, and seek to employ fluent Pasifika language speakers, particular those working with infants and toddlers, the most formative years. We need to advocate for parents and whanau to have the opportunity to foster language in the home, rather than be forced into employment, so that children will not be denied the right to grow up safe and secure, surrounded by their home languages.

We need to look beyond the entertainment and sporting aspects of Pasifika culture, and see Pasifika children as the future doctors, lawyers, engineers, academics, catalysts for change and leaders of tomorrow.

Because embedded in language are the seeds of greatness.

"Ko taku reo taku ohooho, ko taku reo taku mapihi mauria"

My language is my awakening, my language is the window to my soul

Comments

Post a Comment